What Are Constraints in Engineering - Overcoming Design Barriers

Constraints in engineering define the conditions a design challenge must comply with. Constraints impact the final product and must be considered before every project.

Objectives are the desired features that set the target, while constraints set the boundaries or frontiers of design. Without limitations, a design task may seem open-ended, but in practice, constraints are what make the problem specific and solvable.

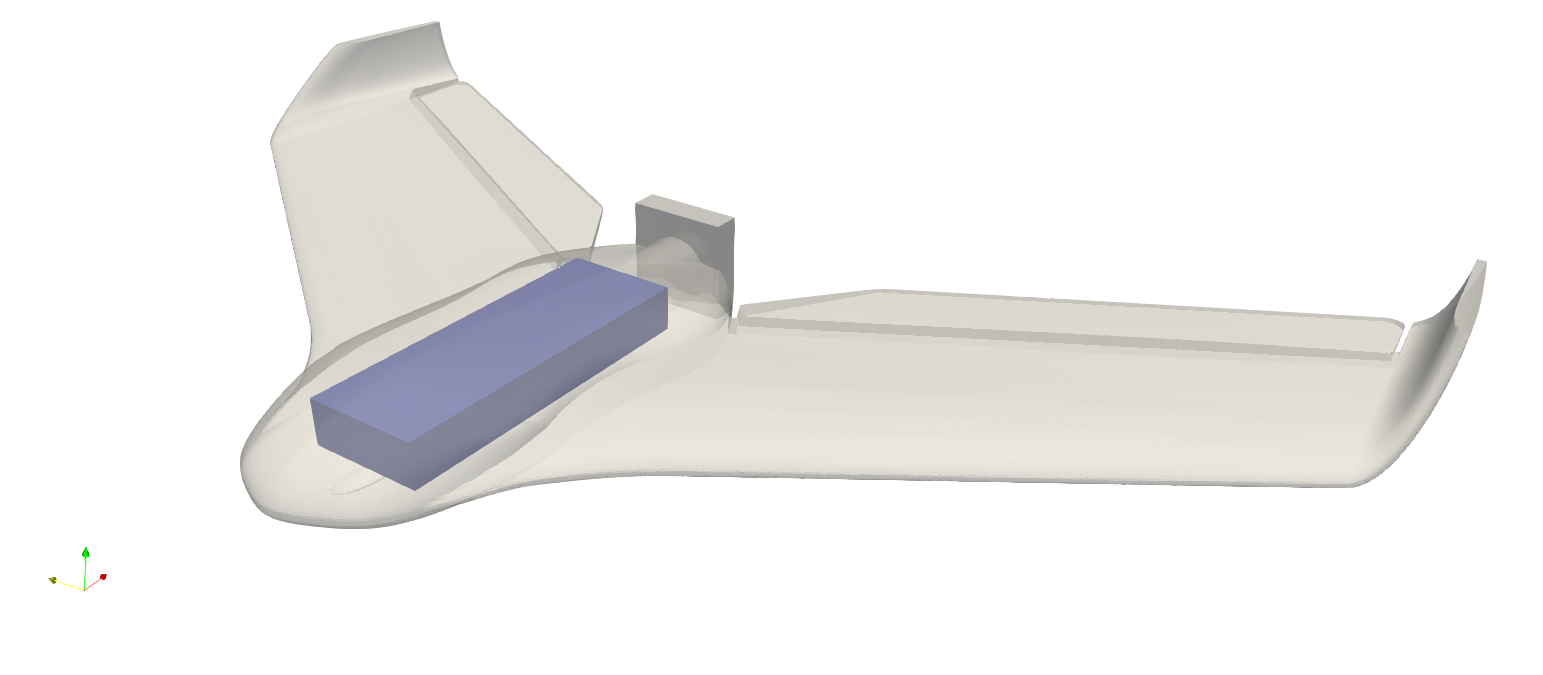

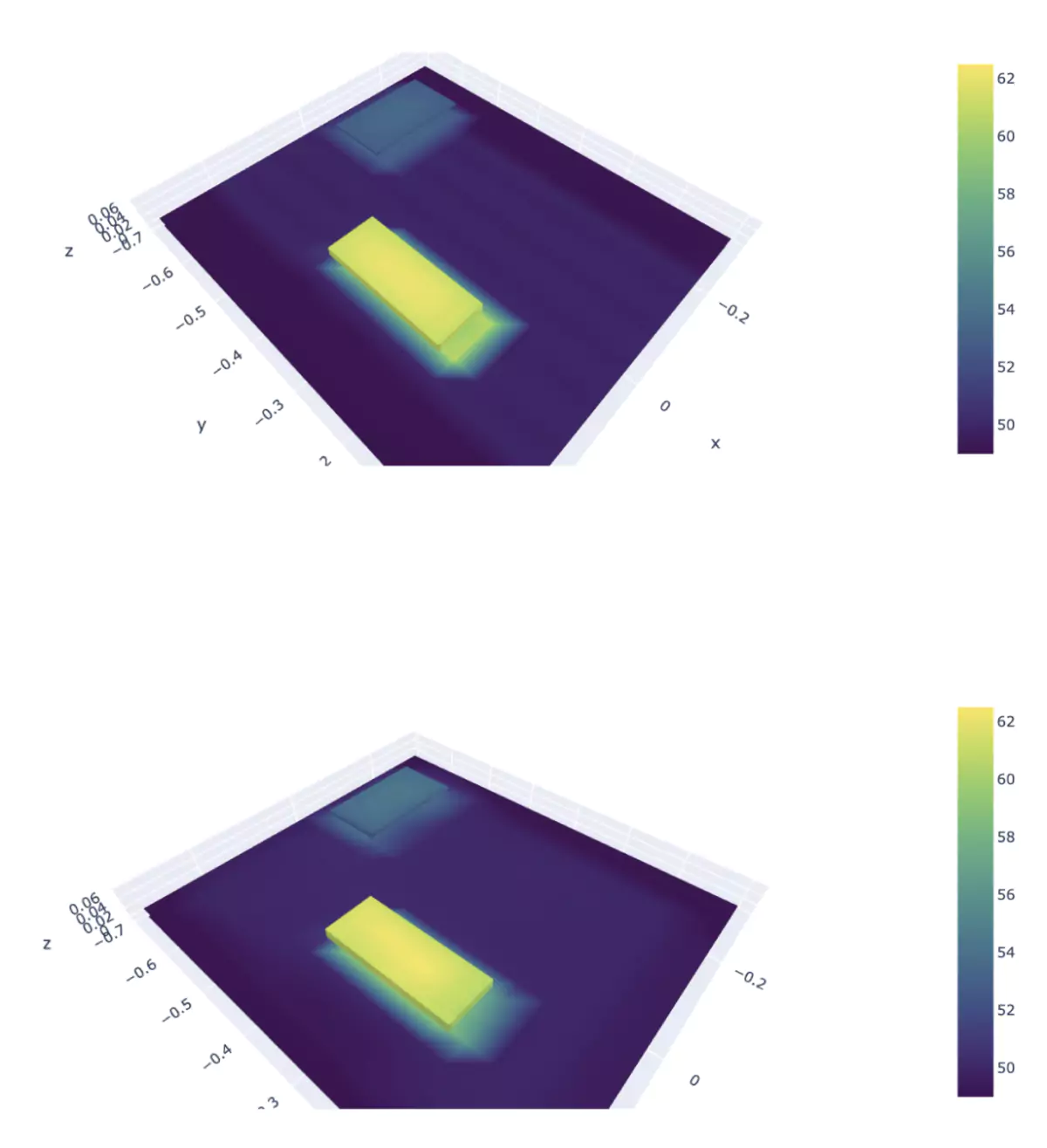

For illustrative purposes, the shown drone dynamics design and optimization case of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) shape includes a box that represents the minimum space occupied by the UAV’s payload.

Want to know more about what are constraints in engineering? The sections below will walk you through the key concepts:

- Types of Possible Constraints

- Why are Constraints Important? With Examples

- Examples of Constraints in Engineering

- What is the Role of Constraints in Design?

- Human-Centered Design Approach

- What is Balancing Criteria in Engineering?

- Specific Constraints in Engineering: Case Studies

- Criteria and Constraints

- How AI is Helping Constraint-Driven Design in Engineering

Types of Possible Constraints

Constraints can take many forms, depending on the nature of the project. Common categories include:

- Physical, such as size, weight, or material properties

- Technological, related to available manufacturing processes or tools

- Economic, including cost limits or resource availability

- Regulatory and safety measures imposed by laws, standards, or risk assessments

- Environmental factors, such as energy consumption or emissions

Constraints in engineering design can be categorized into several groups, each influencing the set of acceptable solutions in distinct ways:

Physical

These include measurable boundaries imposed by the physical world, such as overall dimensions, weight, material strength, thermal behavior, and the geometry of the environment where the object must fit or operate.

Technical

They stem from current capabilities in manufacturing, tooling, and materials. For instance, a design may be limited by machining tolerances, available joining methods, or the maximum load a component can withstand without failure.

Economic

These refer to the financial boundaries of a project. They include cost ceilings for materials, labor, equipment, and long-term maintenance. A design must meet objectives without exceeding the budget.

Time

Design engineers work under fixed schedules that may be derived from contractual deadlines, production cycles, or market timing. These limitations affect the extent to which testing, iteration, or optimization is possible.

Regulatory

Compliance with laws, codes, and safety standards is required, influencing design decisions related to structural integrity, emissions (e.g., pollutants or noise from vehicles or machinery), and accessibility (e.g., inclusive design for individuals with disabilities).

Environmental

These address the ecological impact of a solution during both production and use. They involve resource sourcing, energy consumption, recyclability, or restrictions on pollution and waste.

Why Are Constraints Important?

Constraints are extremely important because they shape design decisions from the very beginning, leading to success. They filter out unworkable ideas and define the conditions a solution must satisfy to be viable, safe, and effective.

- Ensure Feasibility

- Constraints help engineers identify what is technically and physically possible. For example, a drone design may be limited by battery energy density, which directly affects flight time and payload capacity.

- Guide Design Choices

- Constraints direct the selection of materials, geometry, and manufacturing methods. For example, if a component must withstand high temperatures, the material must be thermally stable, ruling out many polymers and low-grade metals.

- Foster Innovation

- Strict limitations often push engineers to find creative alternatives. For instance, weight limits in aerospace led to the widespread adoption of carbon-fiber composites as a replacement for heavier structural metals.

- Ensure Practicality

- Designs must be producible, maintainable, and operable. In automotive design, engine components must not only function under high stress but also be easily assembled and replaced within standard service intervals.

- Promote Safety

- Regulations impose restrictions to prevent harm. In electrical engineering, maximum leakage currents and insulation distances are specified to protect users from electric shock and prevent short circuits.

Examples of Constraints in Engineering

Constraints appear in every design context and must be addressed early. They define what is acceptable, possible, and compliant with the surrounding environment and objectives.

Building a Skyscraper

When designing a skyscraper, engineers must consider several key factors that shape the building’s structure and layout. These include:

- wind loads, which affect stability;

- soil bearing capacity, which determines the foundation type;

- column spacing, which influences floor plans; elevator core size, which impacts vertical movement;

- seismic codes, which ensure the building can resist earthquake forces;

- and vertical transportation efficiency, which optimizes occupant flow.

Together, these internal and external constraints guide the choice of structural system, foundation design, and overall floor layout, ensuring safety and resilience.

The listed constraints form a diverse set because they originate from distinct categories.

Designing a Smartphone

Constraints on a smartphone design include at least:

- overall dimensions,

- battery capacity,

- screen-to-body ratio,

- heat dissipation,

- durability under drops,

- and component cost.

Engineers must balance the above considerations with size, weight, and affordability, without sacrificing usability.

Developing a Dialysis Filter

Constraints include the biocompatibility of materials, filtration efficiency, flow rate, sterilization compatibility, and adherence to patient safety regulations. The filter must perform reliably while avoiding immune reactions and meeting the standards of medical devices.

What is the Role of Constraints in the Design Process?

Constraints define the internal and external factors that engineering solutions must consider while striving to meet project goals. They are not obstacles to avoid, but essential parameters that shape the design process. A design is considered valid only if it meets both the objective and all the applicable constraints.

Design Constraints

Design constraints are limitations or restrictions that influence the engineering design process and its outcome.

They can be internal or external, affecting the project’s scope, cost, and functionality.

They include material availability, budget, and environmental standards. Designers must consider these early when generating ideas and with creative thinking solutions, as they directly impact the final product and shape the project from start to finish.

Main Types of Constraints

Design constraints can be grouped into broad categories, each with a distinct impact on how engineers approach a solution. Here are six key types, with practical examples for each:

- Physical constraints - Limits on size, mass, or spatial arrangement. E.g. "The device must fit within a 482.6 mm (19”) rack unit or "The system weight must not exceed 500 kg."

- Technical constraints - Requirements tied to materials, tolerances, performance, or manufacturing. E.g. The casing must withstand 200 °C without deformation."

- Economic constraints - Restrictions related to cost or resource use. E.g. "The assembly must take less than 10 minutes."

- Time constraints - Deadlines or timeframes for delivery and development. E.g. "The tooling must have a lead time under 60 days."

- Regulatory constraints - Compliance with laws, standards, or certifications. E.g. "The product must meet CE marking and RoHS compliance."

- Environmental constraints -мSustainability, resource, or operating condition limits. E.g. "The equipment must operate between −20 °C and +60 °C."

How Constraints Shape Creativity and Decision-Making

Far from limiting creativity, constraints focus it. They eliminate arbitrary choices and compel designers to justify their decisions. In many cases, working within strict constraints leads to simpler, more efficient, or more elegant designs. Constraints challenge design teams to think differently and can stimulate innovative solutions by forcing new approaches within defined boundaries. This focus helps ensure solutions are both practical and inventive. Understanding constraints enables engineers to source the right people for project tasks.

Practical Implications

Identifying constraints early, analyzing their impact on design problems, and incorporating them into design iterations is a fundamental engineering skill.

Ignoring or underestimating constraints leads to failure, resulting in solutions that are too expensive, impossible to manufacture, unsafe, or non-compliant. Therefore, engineers must treat constraints not as afterthoughts, but as core design inputs from the start.

Human-Centered Design Approach

Human-centered design is an engineering approach focusing on real users and their contexts, including environmental impact. Instead of just focusing on technical performance or cost, it begins with understanding user interactions, tasks, constraints, and experiences. It’s a structured, measurable process that enhances technical performance and user acceptance. A product ignoring human use cases, even if functionally complete, often fails in practice.

The Human-Centric Approach

The process involves observing users in their environment, identifying functional and ergonomic requirements, and translating those into measurable design specifications. These engineering design principles are at the heart of modern constraint-driven design practices that integrate human factors and system-level requirements. This includes physical factors such as reach, force, posture, and interface layout, as well as cognitive factors like workload, clarity of feedback, and error tolerance.

Human-centered design is crucial for products that involve frequent or safety-critical interactions, such as medical devices or control panels. For instance, surgical instrument design must prioritize usability under time pressure, glove compatibility, and cleaning.

Key Technical Considerations

Key technical considerations include:

- Accessibility: Can users with physical or sensory limitations operate the product without additional tools or help?

- Usability: Can users complete tasks accurately and efficiently without repeated trial-and-error?

- Aesthetics and perception: Does the product convey trust, reliability, and purpose through its shape, materials, and interaction model?

Engineers must reconcile human factors with other constraints (mechanical, electrical, environmental) and technological design through iterative prototyping and testing. The goal is not to add user-friendliness at the end but to embed it from the beginning as part of the system’s function and reliability.

What is Balancing Criteria in Engineering?

Balancing criteria in engineering means managing trade-offs between multiple competing goals in a design.

Successful engineering design involves balancing both criteria and constraints.

While objectives define what the design solution should achieve, constraints define what must not be violated; thus, they serve as fixed reference points during the design process.

Together, the two factors create the space where feasible options exist, i.e., the design space to explore.

Balancing criteria in engineering involves a multi-objective optimization of parameters that cannot all be maximized simultaneously, e.g.

- Minimize material cost,

- Minimize structural weight,

- Maximize load-bearing capacity,

- Maximize durability against environmental factors.

This competition between contrasting objectives requires prioritizing and adjusting design objectives to meet overall project requirements. Improving one aspect, such as increasing a beam’s thickness for increased strength, often affects others, including weight and cost. The aim is to find an optimal balance that satisfies critical objectives without maximizing any single attribute.

Available Tools

Engineers use tools such as multi-objective optimization, design matrices, and simulation-based trade-off studies to evaluate alternatives. Decisions must be justified with data, not guesswork, and aligned with project priorities—whether that means minimizing lifecycle cost, meeting strict safety margins, or delivering within a fixed timeline.

Unleash efficient design with topology optimization for efficient design.

More Details on Available Tools for Balancing Criteria

Balancing competing design criteria requires structured methods to explore trade-offs and identify viable solutions. Here are several commonly used tools:

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)

Engineers define several objective functions—such as minimizing weight and cost while maximizing strength—and use algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms, Pareto optimization) to find solutions that offer the best compromise. This approach is essential when no single “best” solution exists. You can explore how optimization cases are solved with Machine Learning.

Why MOO is Critical for Engineers

MOO is indispensable in engineering because real-world problems rarely involve a single goal. For instance:

- Aerospace: Designing aircraft wings to minimize drag, weight, and fuel consumption while maximizing lift and structural integrity.

- Automotive: Optimizing vehicle chassis for crash safety, fuel efficiency, and production cost.

- Civil Engineering: Balancing cost, environmental impact, and load capacity in infrastructure projects.

- Electronics: Designing circuits to minimize power consumption and heat generation while maximizing performance and reliability.

The absence of a single “best” solution in MOO reflects the complexity of engineering trade-offs, where decisions impact performance, cost, and sustainability.

Sensitivity Analysis

This technique helps determine how sensitive a system’s performance is to variations in inputs or parameters. It is critical when specific criteria, such as thermal limits or tolerances, are more restrictive than others. This ensures a more accurate evaluation of the system’s behavior under varying conditions.

Design of Experiments (DoE)

A statistical approach that systematically varies inputs to identify combinations that yield the most favorable outputs. DoE is often used in aerospace and automotive sectors where test budgets are tight but multiple objectives must be met.

Specific Constraints in Engineering: Case Studies

Constraints are not generic limits—they are often project-specific, tightly tied to materials, environments, or regulatory frameworks. Below are real-world examples showing how specific constraints shape engineering outcomes.

Thermal Constraints in Spacecraft & Aerospace Design

- In satellite engineering, thermal constraints are critical. Electronics in orbit experience extreme temperature fluctuations (from +120°C in sunlight to −100°C in shadow). Engineers must design thermal control systems that utilize multi-layer insulation and radiators to maintain components within their operating ranges. Material choices are restricted to those with stable thermal expansion and low outgassing. Discover how Neural Concept’s platform enables the design of smarter satellites.

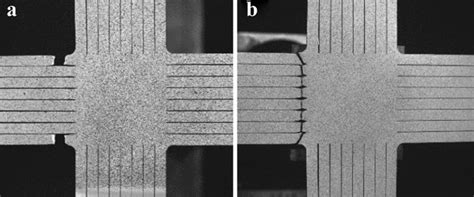

- Aircraft components, especially in the wing root and landing gear, must endure millions of load cycles. Constraints related to fatigue life limit design geometry, impose strict tolerances on surface finish, and require specific alloys, such as 7075-T6 aluminum. Designs are validated through accelerated fatigue testing and crack-propagation models.

Sterilization Constraints in Medical Device Design

- Surgical instruments and implantable devices must survive repeated sterilization without degrading. Materials must withstand autoclaving (typically 134 °C, saturated steam, high pressure) or chemical exposure. These constraints rule out many polymers, dictating the use of titanium, PEEK, or specific grades of stainless steel.

- Pacemakers and insulin pumps must fit inside the human body with minimal intrusion. Size and weight constraints limit battery capacity, component size, and the design of wireless antennas. Engineers must use ultra-low-power electronics and energy harvesting where possible to stay within dimensional limits without compromising function.

Soil Bearing Constraints in Foundation Engineering

When designing foundations for bridges or tall buildings, engineers must consider the local soil's bearing capacity. For example, clay-rich soil may limit the use of shallow foundations, forcing the adoption of deep pile systems. Constraints such as settlement rates and lateral pressure impact both safety margins and construction methods.

Water Use Constraints in Cooling Systems

In industrial facilities located in water-scarce regions, process cooling systems must minimize water use due to limited freshwater availability and strict regulatory limits (e.g., U.S. EPA water usage guidelines). This constraint often drives the adoption of closed-loop systems, which recycle ~95% of water, or air-cooled heat exchangers, which eliminate evaporative losses.

Engineers must balance thermal efficiency (e.g., achieving high heat transfer coefficients), pump power (e.g., minimizing energy use, typically 10-20% of system costs), and heat exchanger size within strict environmental regulations and capital/operational cost limits.

Criteria and Constraints

In engineering, defining a problem involves more than describing what to build—it requires clear objectives (criteria), legal considerations, and strict limits. These shape the solution space and guide design and optimization. A solution that meets all limits but fails key criteria is useless, just as a design that achieves performance goals but violates safety or cost limits is unfeasible.

Balancing criteria and constraints is the core of design optimization by engineers.

Design Criteria

Criteria define the functional goals and performance targets that the solution must achieve. They are measurable, testable, and used to compare alternative designs.

Criteria are the targets to optimize for—either to maximize (efficiency, strength) or to minimize (weight, energy use, noise).

Typical design criteria include:

- Performance Criteria: How well the system carries out its intended function (e.g., power output, speed, efficiency)

- Durability Criteria: Expected lifespan under normal operating conditions

- User interaction: Ease of use, clarity of interface, and ergonomics

- Maintainability Criteria: Ease of servicing, inspection, and component replacement

- Cost-effectiveness: Total cost of ownership, not just initial manufacturing

- Aesthetics and form: Where relevant, these criteria address the visual and tactile qualities of the product, including resource selection, design appeal, and user interaction.

Design Constraints

Constraints define the boundaries within which the design must operate. Unlike criteria, they are absolute: violating a constraint makes a solution invalid, regardless of its performance. Constraints are not just checkboxes—they directly shape what kinds of solutions are even possible. A strong engineering design process includes systematic identification of constraints early on, followed by iterative testing to ensure compliance as the design evolves.

Common constraints include:

- Physical limits: Size, weight, available space, or mass

- Material limits: Strength, thermal resistance, corrosion resistance

- Budget and resource limits: Cost ceilings, labor availability, supply chain constraints

- Time constraints: Project deadlines, development cycles

- Regulatory requirements: Safety codes, environmental limits, industry standards

How AI is Helping Constraint-Driven Design in Engineering

AI cannot remove constraints. It turns them into inputs that guide the design from the beginning. Instead of checking for violations at the end, engineers now use AI to explore what’s possible within those limits—quickly, precisely, and with less trial-and-error. Learn more about Transforming Engineering Design with AI here.

AI-Powered Simulation Tools

Platforms like Neural Concept utilize geometric deep learning to accelerate simulation. These models predict physical behavior, such as pressure or temperature fields, directly from 3D shapes.

Engineers can instantly test if a design stays within thermal or aerodynamic limits, without running complete finite-element solvers. This means constraints are respected as the design evolves, not patched in later.

Discover how to revolutionize your design process with the AI-first engineering platform for product development.

Design Constraints: Sensitivity Analysis with Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of artificial intelligence that enables computers to find patterns and make predictions from data without explicit programming. In engineering, ML models analyze large datasets from simulations or experiments to identify which design constraints have the most significant impact on performance.

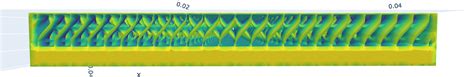

For example, when optimizing a heat sink, the design criteria might include maximizing cooling efficiency and minimizing weight.

Design constraints could be maximum size, manufacturing cost, and allowable material types. An ML model trained on past designs can demonstrate that small changes in fin geometry have a more significant influence on heat dissipation than swapping between available materials. This insight helps engineers focus their efforts where they will have the most considerable effect, avoiding exhaustive testing of less critical variables.

Iterative Design with AI Feedback

Real-time AI feedback allows faster design iterations. Engineers can tweak geometry and immediately see whether stress, mass, or drag stays within the required bounds. This shortens the cycle from concept to feasible design, avoiding time wasted on dead-end ideas.

FAQs

What are the different types of design constraints in mechanical engineering?

Mechanical engineering constraints encompass physical (size, weight), material (strength, fatigue), thermal (expansion, heat dissipation), manufacturing (tolerances, processes), economic (cost, time), and regulatory (safety standards, industry codes) considerations.

How do constraints impact the engineering design process?

Constraints define the feasible solution space for various design projects. They filter out invalid options and force trade-offs between competing objectives. Constraints must be respected throughout design, analysis, prototyping, and testing to ensure a workable and compliant result.

What are examples of physical constraints in civil engineering projects?

Typical physical constraints include soil bearing capacity, maximum span length, material strength, seismic loads, allowable settlement, and clearance requirements. These directly affect structural choices and construction methods.

How are constraints handled in the software engineering design process?

Software constraints include memory, processing time, hardware compatibility, and network bandwidth. They are managed through code optimization, modular design, resource monitoring, and early definition of system requirements.

What are the economic constraints involved in large-scale engineering projects?

These include capital expenditure limits, labor and material costs, project timelines, the cost of delays, supply chain volatility, and return on investment expectations, which are essential for high school students to understand. Cost modeling and risk assessment help manage them.

How to identify constraints in an engineering design process?

Start with stakeholder requirements, site or system limitations, regulatory documents, and available resources. Use a constraint matrix or checklist during early planning and update it during iterations.

How can I balance thermal, structural, and weight constraints when designing compact components?

Use multiphysics simulation tools to analyze trade-offs. Select materials that perform across all domains (e.g., high strength-to-weight ratio and good thermal conductivity), and explore integrated cooling or lightweight stiffener.